Volunteer doctors work to provide universal healthcare

Tran Phuong, a teacher at the Da Nang-based Hung Vuong Primary School used to frequently suffer from sore throat.

|

| Teamwork: John Masud Parvez (centre) stands with other members of the Viet Nam Social Health Revolution. The organisation aims to develop a healthier Viet Nam. — Photo from Facebook of John Smith |

After several days of canker sore in her mouth, she sought advice on her condition from the Viet Nam Healthcare Support, a public group on Facebook providing advice on health and nutrition.

After following the advice from specialists in the group - avoiding hot and spicy food, eating soft food and applying ointment containing Triamcenolone twice a day - her condition improved.

Since it was launched in May last year, the Viet Nam Healthcare Support, with 15 Vietnamese specialised doctors, has offered free consultation to many Facebook users via its group page. The page also serves as an open platform to discuss and share useful information about health, nutrition or medicine.

The Viet Nam Healthcare Support is among 14 medical projects of the Viet Nam Social Health Revolution (VSHR), a social organisation established by John Masud Parvez from Bangladesh, who works as head of project development at RMIT University.

Parvez’s passion is research. He is involved in research work even when he is working in the technology and consulting industry. He has had some nine conferences or journal publications on his work.

“I was a bit disappointed that my research work was all going to industry, making the industry better and more effective. I wanted to do something for the society or for people with low income. I was thinking about what I could really do with my technology background,” says Parvez. He has been living in HCM City for more than 6 years and calls the city his second home.

One incident that significantly changed his philosophy and thoughts was when he was infected with sinusitis while working at RMIT University. He fell sick for 7 months.

“I was so desperate that I went to international hospitals, local hospitals and doctors’ homes. I paid 15 million VND (659 US$) for one visit to a doctor, which is higher than the monthly salary of a local university graduate. I finally recovered after visiting a friend-recommended doctor who worked at a local hospital. During my long treatment period I had a close experience of the health system in Viet Nam,” says Parvez.

“If other neighbouring countries like Thailand and Malaysia can have quality health service models, so can Viet Nam,” he says.

As soon as Parvez recovered, he formed a small group of volunteers and conducted health-related research from 2013 to 2017. During the four years, he interviewed some 25,000 Vietnamese and 4,000 doctors in different cities across the country. By early 2017, they had compiled data and analysis to publish their work. Incidentally at that time, VSHR was also founded.

Parvez and his group’s research points out the many issues with public health. One of them is that there is no sustainable and smart health awareness development framework and approach for students, the future of Viet Nam. Moreover, people with low income neither have a proper health development approach nor quality health service model in their income range.

“Most of the people do not know how to maintain good health or follow a healthy diet. They get information about health from the wrong sources. When they have health problems, they tend to go the pharmacist and buy medicine directly without seeking medical advice from a doctor. The pharmacists usually sell high doses of strong medicines, which create drug resistance in people aged 27 or above,” Parvez says.

“VSHR’s vision is a healthier Viet Nam, with quality support framework for people who have low income,” he adds.

VSHR currently has some 150 members, half of whom are medical professionals. It runs 14 projects with a sustainable approach, such as health facilities for orphans, medical advice for low-income groups and health education and training to students.

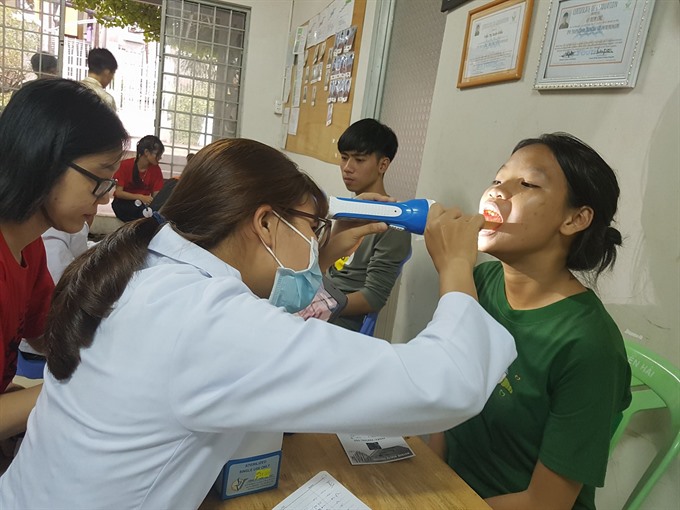

|

| Say aaaah: Doctors participating in the Vietnam Social Health Revolution examine children under one of the projects of the organisation. — Photo from Facebook of Viet Nam Social Health Revolution |

In 2017 alone, VSHR offered medical assistance to some 100,000 Vietnamese. It is expected to help 500,000 people this year.

“In big hospitals, there is a huge number of patients coming in every day, so the doctors do not have much time to thoroughly explain to the patient his/her situation. For example, patients with chronic diseases lack understanding about their conditions, which makes them feel more worried,” says Le Thao Hien, a doctor of dermatovenereology at HCM City hospital. “When their inquiries are resolved after consulting VSHR, they feel more secure about their treatment and conditions.”

VSHR’s work is not limited to southern Viet Nam alone. Parvez is working on scaling up all projects to bring them to every person in the country gradually.

“Northern Viet Nam is one of the 4 priorities in expanding our support to far-off places, such as Sa Pa, and nearby areas in which there are many disadvantaged people in need of medical help,” Parvez says.

Further details about VSHR’s projects are available on the website: www.healthrevolution.cf.

(Source: VNS)