Phan Khoi – The man who loved to debate

One of the most distinctive traits of the people of Quang Nam is their tendency to reason, debate, and challenge ideas—in simple terms, they love to argue. This characteristic is so well recognized that it has given rise to a widely known saying: “Quang Nam hay cai” (Quang Nam people love to argue).

|

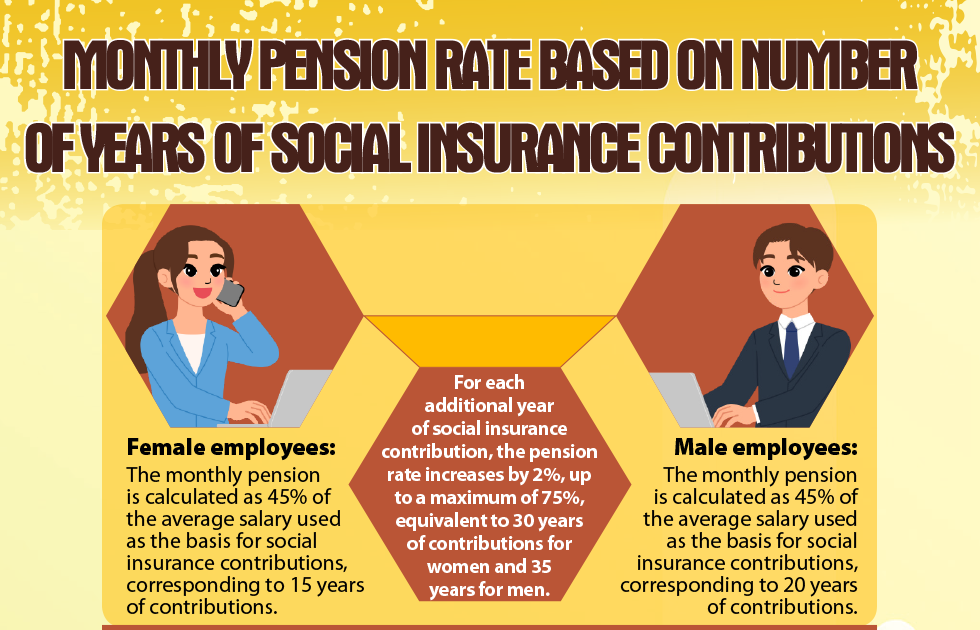

| Journalist Phan Khoi delivering a speech at the ceremony commemorating the 20th anniversary of writer Lu Xun's passing. Photo: Archival material. |

"Arguing" (or "debating") refers to using reasoning to refute others' opinions and defend one's own viewpoint. Scholars such as Nguyen Van Xuan, writer Nguyen Ngoc, and researcher Ho Trung Tu have analyzed in great depth the origins and defining traits of the Quảng people's well-known tendency to engage in debate, often described as "Quang Nam hay cai" ("Quang Nam loves to argue").

One of the most notable figures embodying this trait is writer and journalist Phan Khoi (1887–1959). Born in Bao An Village—now Dien Quang Commune, Dien Ban Town, Quang Nam Province—he made his mark in Vietnamese literary history as the pioneer of the "New Poetry" movement with his famous poem Tinh gia ("Old Love"). Phan Khoi was known for his relentless debating spirit, which manifested in nearly every aspect of his life, but was most strikingly displayed in his literary polemics.

In Vietnam during the 1930s, a series of fierce and heated literary debates took place—unparalleled before and rarely seen afterward. These intellectual battles helped clarify many pressing theoretical and practical issues of the time. Researcher Thanh Lãng referred to these debates as “vu an” (literary cases). According to him, there were a total of ten major literary disputes during this period, namely:

1. The Press; 2. Tradition vs. Modernity; 3. Phan Khoi vs. Tran Trong Kim; 4. Tan Da vs. Phan Khoi; 5. National Studies (Quoc hoc); 6. Classical Poetry vs. New Poetry; 7. Idealism vs. Materialism; 8. Art for Art’s Sake vs. Art for Life’s Sake; 9. The Case of Teacher Minh and La ngoc canh vang (Jade Leaves, Golden Boughs); 10. Han Mac Tu.

During this period, two figures built their careers primarily through literary debates: writer and journalist Hai Trieu (father of poet Nguyen Khoa Diem) and writer and journalist Phan Khoi. Notably, among the ten major literary disputes mentioned earlier, Hai Trieu participated in only two—the seventh (Idealism vs. Materialism), in which he debated Phan Khoi, and the eighth (Art for Art’s Sake vs. Art for Life’s Sake), where he confronted Thieu Son. In contrast, Phan Khoi took part in seven of these debates (from the first to the seventh), and what is particularly remarkable is that he was the initiator of most of them, often sparking and leading the intellectual clashes.

Most of Phan Khoi’s intellectual adversaries in these literary debates were esteemed scholars, including Tran Trong Kim, Huynh Thuc Khang, Pham Quynh, Tan Da, Tran Huy Lieu, Hai Trieu, and Le Du. His polemics spanned a wide range of subjects, from culture, ideology, and philosophy to literature, the arts, history, and social issues. Once engaged in a debate, he argued with unwavering intensity and rigor, often forcing his opponents into a corner, unable to defend their positions. His exchanges had tangible effects—after debating with Phan Khoi, scholar Tran Trong Kim had to revise his work Nho Giao (Confucianism) for its reprint. Even Huynh Thuc Khang had to concede, remarking, “Having my mistakes pointed out by him is a fortunate thing for me!”

To amass the vast and profound knowledge necessary for debating and engaging in literary polemics with esteemed scholars, Phan Khoi demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for self-study, when in terms of formal education, he held only a “tu tai” in classical Chinese studies.

A passionate advocate of logic, Phan Khoi placed great emphasis on reason, using logical argumentation to defend his viewpoints. In debates and polemics, he never hesitated or showed favoritism, refusing to let personal relationships influence his intellectual battles. For instance, despite journalist Huynh Thuc Khang being a fellow countryman and senior figure in the Duy Tan reform movement, Phan Khoi engaged in fierce debates with him on five separate occasions. Similarly, he clashed with scholar Le Du—who was not only a prominent intellectual but also his own brother-in-law—without yielding an inch for the sake of family ties. Prioritizing truth over personal feelings, Phan Khoi's philosophy echoed that of the ancient Greek thinker Aristotle, who famously declared, “Plato is my teacher, but truth is dearer to me.”

After 1954, while working in the field of culture and the arts in northern Vietnam, Phan Khoi became involved with the Nhan Van - Giai Pham movement, emerging as one of its key figures. In his essay "Criticism of Literary Leadership," he provided a detailed and candid critique of the lack of transparency and democratic principles in artistic and literary activities, advocating for greater creative freedom for writers and artists. This piece stands as one of the most striking examples of Phan Khoi’s renowned argumentative nature—an embodiment of his unwavering honesty, and fearless integrity.

In a different context, this could have been a lively, engaging topic for a spirited debate, attracting many participants. However, due to the specific circumstances at the time, no debate or argumentation took place. Phan Khoi passed away in 1959. Due to the war, his grave at the Hop Thien Cemetery in Hanoi was lost. After the reunification of the country, his descendants went to the cemetery and gathered a handful of symbolic soil to create a memorial grave in his hometown in Quang Nam.

The tendency to "argue" among intellectuals and elites is, in essence, a form of social criticism. Arguing/criticizing is the best way to clarify issues and approach the truth, serving as a crucial driving force for societal progress.

To engage in debates or criticism aimed at promoting societal development requires contributions from both sides: the debater and the social environment in which the debate takes place. The debater must first possess deep, broad, and erudite knowledge. More importantly, they must have the courage and resilience to face opposition, unafraid of conflicts or losses. When necessary, they must be willing to sacrifice material and emotional interests to defend their point of view.

The history of Quang region is filled with such exemplary figures, such as Minister Pham Phu Thu, who boldly disagreed with Emperor Tu Duc and was exiled to serve as a horse grass-cutter; the leaders of the Duy Tân movement, who opposed the colonial and feudal regimes and were imprisoned or sacrificed, including Tran Quy Cap, Phan Chau Trinh, and Huynh Thuc Khang. In addition to the courage and determination of the debater/critic, another crucial factor is the need for a truly democratic and healthy environment, where those in power must be open-minded, willing to listen, and receptive, especially when the debater/critic presents well-founded and convincing arguments.

It can be said that the inherent nature of the people of Quang region is their tendency to argue, and the arguments of the intellectuals and elites are, in essence, a form of social critique—a vital element for accessing truth and fostering societal development. The writer and journalist Phan Khoi is a prime example of this.

Reporting by People’s artist HUYNH HUNG – Translating by HONG VAN