When museums tell stories

It was a cold, rainy winter afternoon in 2023 when I stepped out of the Salon de Livre book fair—an event with a long-standing history in France, dedicated to young adults, and held annually in Montreuil, a suburb of Paris. My mind was still lingering on the conversations about publishing, books, and the young crowds packed into the booths of various publishers, eagerly waiting for authors to sign their books. The sky was still bright, and I decided to look for a nearby museum to visit. Coming to France, a "paradise" for museums and archives, the opportunity to explore such places is always something I eagerly anticipate.

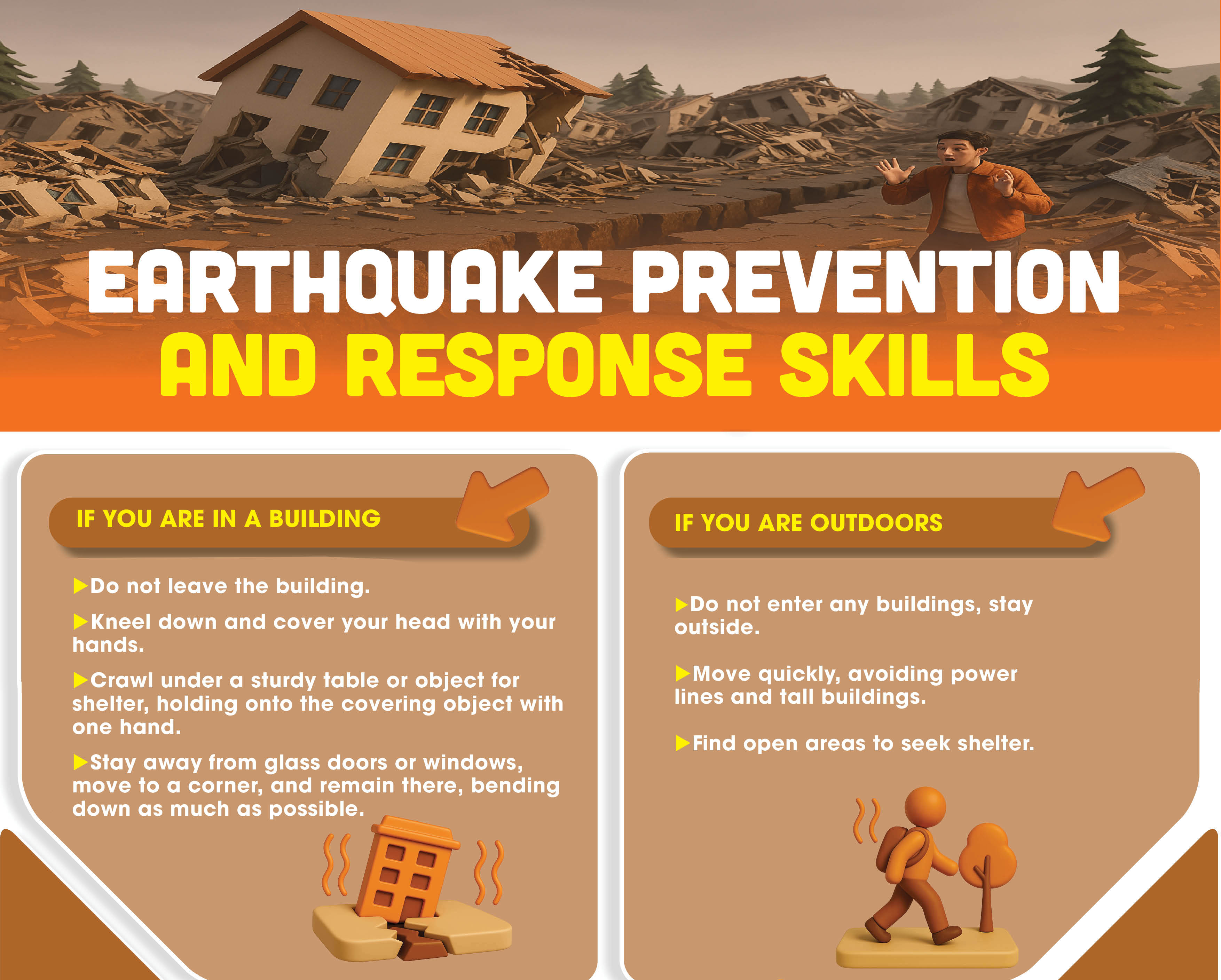

|

| The exterior view of the National Museum of the History of Immigration (France). Photo: T.H.P. |

Creative and vibrant

The area where I live, Montreuil, is a diverse region with many immigrants, representing various ethnicities and religions. The Muslim community is quite large, and there are numerous eateries following Islamic traditions. I feel that this place, like other immigrant neighborhoods, is filled with more street-side shops, offering a more diverse life. You can find many workers, fruit stalls, grocery stores, leather goods shops, and more, all spilling out onto the streets. In the evenings, figures quietly emerge from the metro stations. They work in Paris and then head home after a packed train ride.

Amidst this atmosphere, the presence of a museum named the Musée national de l'histoire de l'immigration (National Museum of the History of Immigration) immediately caught my attention. Perhaps, to truly understand the core issues within French society, approaching them through the lens of immigration history is indispensable.

That afternoon was spent wandering through a space steeped in history, art, and anthropology, all deeply evocative. The exhibits and stories reflect the history of immigration to France, dating back to the late 18th century, when the first waves of immigrants began to arrive. The museum places a special emphasis on the major waves of immigration during the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly from France’s former colonies, such as North Africa, West Africa, and Southeast Asia.

The dramatic chapters of history, with many different peoples and their displaced fates, are depicted. These people have identities uprooted and then they cast adrift to a distant and unfamiliar land. The exiled lives are solitary, and while some stories end on a hopeful note, they are still tinged with an indescribable melancholy. Today, all of these people have become a part of France, both absorbed into and contributing to the present French identity.

| I believe that if children were to visit places like this, history would become something tangible, something personal and deeply emotional. It would spark their curiosity to learn more about these figures, and from there, they would develop stronger feelings and drive. And I dream of a day when the stories of our own history, culture, and indigenous languages—of a country with a rich and diverse cultural heritage, full of the vibrant colors of the tropical land—will be heard in a way that is truly worthy of them. |

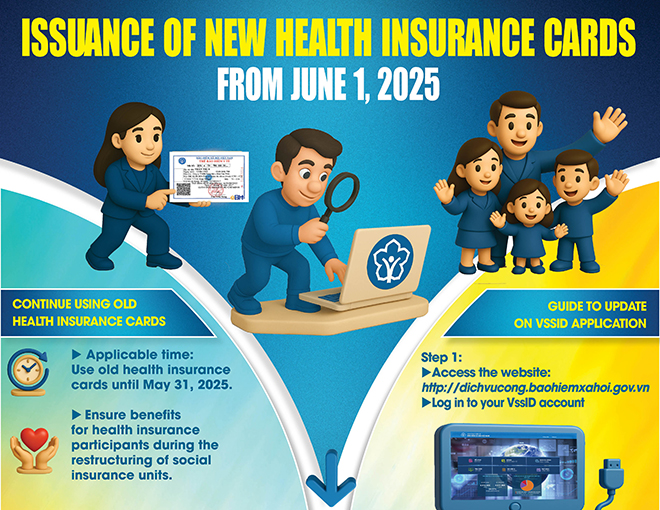

Immediately after, walking along the street that faces the Chaillot Palace, across from the Eiffel Tower, I entered the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Mankind) and was immediately drawn into a fascinating and dynamic narrative of human history—vast in scope and captivating in detail. This museum is one of the most important in the world for anthropology, archaeology, and the prehistory of humankind.

Founded in 1937, the museum is part of the National Museum of Natural History of France and focuses on recreating the evolutionary history of humans, the cultural diversity, and the heritage of civilizations across the globe. With a rich collection of over 30,000 artifacts, the Musée de l’Homme showcases archaeological specimens, fossilized bones, prehistoric tools, as well as cultural artifacts reflecting the lives of indigenous communities from various parts of the world.

Some of the key exhibits at the museum include the skull of a Cro-Magnon man, prehistoric artworks from caves, and ethnographic collections from across the continents. Additionally, the museum features modern exhibition halls where visitors can explore topics such as genetics, language, and the impact of humans on the environment. Here, the story of humankind is told through a different lens: not through political chronicles, but through biology, language, culture, and anthropology, arranged along a timeline that intertwines various perspectives and "narratives" from diverse individuals and communities.

I was particularly drawn to the exhibit on language, where models of tongues were sticking out, each tongue representing an audio recording of a language from around the world, captured in its natural context. It was fascinating to pull on one of these tongues and hear two people, from some distant corner of the world, having a natural, lively conversation.

Here, I noticed many groups of children, either with their schools or with their parents. The children were curious, exploring, interacting, and running around joyfully. Perhaps, in their own natural way, they would come to understand the diversity of life on Earth as well as the cultural diversity within the human world. I believe, spending a day here is worth more than several years of studying evolutionary biology, especially when human history is presented so creatively and vibrantly.

|

| The most striking impression of the Museum of Mankind is its diversity. The museum helps visitors understand the inherent diversity of both nature and humanity. Photo: T.H.P |

Storytelling Space

The museum’s approach to storytelling has brought objects to life, engaging visitors and enhancing educational value. This is an important trend in modern museum design, helping convey messages in a powerful and emotional way.

Instead of displaying objects in isolation, storytelling museums place them within a specific historical or social context. This allows visitors to feel as though they are embarking on a journey of discovery, where each artifact tells its own unique story. For instance, when viewing a prehistoric human skeleton at the Musée de l'Homme, instead of merely learning its age, visitors can understand the life, challenges, and environment of the people from that era.

Stories help the human brain remember better than dry facts. When a museum employs storytelling, visitors can imagine the context, causes, and consequences of events, leading to a deeper understanding of history, science, or art. This is especially important in anthropology or history museums, where the content is often complex and spans across multiple periods.

Organizing a museum around storytelling approach transforms the visit into an adventure and a process of discovery. For example, a museum could recreate the human migration journey from Africa to the rest of the world, guiding visitors through various eras and cultures, rather than simply listing artifacts in chronological order. These stories can be designed from various perspectives, helping visitors find personal connections with the displayed content.

The museum also employs interactive technology, allowing visitors to explore the story at their own pace, creating a unique experience for each individual. Visitors can tap on a touchscreen to view a vividly recreated scene of prehistoric family life, or stand in front of a projection screen to "read" about their own history based on body structure—such as tracing their ancestry to a particular ancient human species.

I suddenly realized something: these museums do not just display artifacts; they are spaces for storytelling. Here, everything is arranged so that visitors can see themselves as part of a much larger narrative.

The National Museum of the History of Immigration tells the story of people caught in the flow of history, those who have contributed to the making of France but are sometimes still seen as outsiders. The Museum of Mankind, on the other hand, tells the story of human diversity, of how each culture and language is a piece of the larger mosaic of humanity. The space, lighting, arrangement, and multimedia technologies all contribute to creating a vivid experience. Both museums invite visitors to become part of these stories, engaging in a dialogue between the individual and the history of society, the history of humankind...

I left Paris with many questions in my mind. France had told me its story through museums, streets, documents, and archives...

I would like to conclude with a small personal experience at the Nguyen Van Huyen Museum, a private museum I had the opportunity to visit, and left a strong impression on me. I still remember the story that Ethnologist Nguyen Van Huy shared with us as we sat in the garden area called the "Garden of Memory". He recalled how he had once hesitated about whether to establish a museum dedicated to his parents, Nguyen Van Huyen and Vi Kim Ngoc. It was during a visit to the Anne Frank Museum in Amsterdam that he received an inspiration, which ultimately led him to make his decision.

At that time, his uncertainty was whether creating a family-oriented museum would lead to criticism, even though Nguyen Van Huyen was clearly a significant cultural figure, and many members of his family had left their mark on history. His experience at the Anne Frank Museum provided him with an approach: to tell the story of his family from a first-person perspective. It would be a museum for personal and intimate history, full of emotions and memories. It is the place where the artifacts would speak to tell the story of a unique family that spanned the course of a century.

And throughout one morning, we traced the history of the family, interwoven with the broader history from the late 19th century to the present. We moved from the first floor to the fourth, in the quiet space of the villa modestly located in the heart of Lai Xa Village, Hoai Duc. The gentle, elegant sounds of French music and pre-war tunes evoked the atmosphere of the 1930s and 1940s. This is perhaps one of the most impressive private museums I’ve ever visited in Hanoi.

I believe that if children were to visit places like this, history would become something tangible, something personal and deeply emotional. It would spark their curiosity to learn more about these figures, and from there, they would develop stronger feelings and drive. And I dream of a day when the stories of our own history, culture, and indigenous languages—of a country with a rich and diverse cultural heritage, full of the vibrant colors of the tropical land—will be heard in a way that is truly worthy of them.

Reporting by TRAN HOANG PHUONG

Director of Omega Vietnam Book Joint Stock Company

Translating by HONG VAN